Freshwater Ponds

Cape Cod has 890 freshwater ponds. The Cape’s natural ponds are the result of the glaciers that left this area 18,000 years ago. Chunks of glacial ice gouged depressions into the substrate, creating “kettle ponds” that are recharged by rain and melting snow. Precipitation saturates the sandy substrate beneath us some 300 feet deep above bedrock. The groundwater that fills these ponds is the same water we use for our drinking water and irrigation. This water connection is why our ponds are called “windows on our aquifer.”

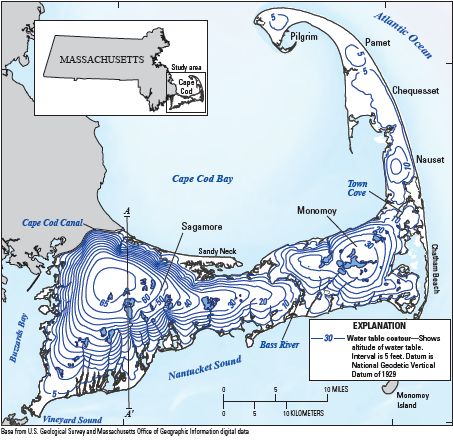

Water is not static. Groundwater moves—it flows. It passes through our ponds on its way to the ocean. A map of the Cape’s groundwater reveals contours—changes in elevation that resemble the irregular surface of the land, although they are not directly related to surface contours.

Most ponds, unaltered by development, are ringed by native woody shrubs like buttonbush, high bush blueberry, and winterberry. These shrubs grow in moist areas, but do not want to be submerged, so the annual high-water level keeps them within a defined edge. Fallen trees and overhanging shrubs give shade, help moderate water temperature in summer months, and provide cover for fish and sunning spots for turtles.

In the shallows of the water, you will find emergent plants like pickerelweed, with its spade-like leaves and purple flower spikes, a favorite of bumblebees. There may be rushes and reeds like woolgrass and pipewort. Submergent plants found in deeper water may include spatter dock, with golden globe-shaped flowers amid large flat leaves, and native white water lilies. Their summer leaves also give shade and help moderate temperature, minimizing algal growth and forming a microhabitat for insects, both above and below the leaves. Fish hide from great blue herons and feed on algae and smaller swimming creatures. Small birds land on floating vegetation to catch an insect or have a drink. The submerged portions of all aquatic plants provide habitat value for numerous invertebrates that are food for fish, ducks, and other wildlife. As fall temperatures arrive, pond vegetation dies back, falling beneath the water’s surface, where the plants’ nutrients are recycled through decomposition.

The water levels in most Cape ponds fluctuate due to changes in groundwater, precipitation, evaporation, and sometimes drawdown by municipal wells. When the shoreline becomes exposed, a coastal plain pond plant community may thrive if it is not trampled or the shoreline otherwise altered by beach fill or structures. This globally threatened habitat of a specialized plant community consists of rose tickseed, grass-leaved goldenrod, Plymouth gentian, and sandplain agalinis. These plants have adapted to the Cape’s kettle ponds, which historically have been low-nutrient, acidic glacial ponds with sand or gravel bottoms.

Threats to Pond Health

The health of our ponds is at risk from past and current agricultural activities, untreated stormwater runoff, invasive species, pollutants from human activities like pesticides and fertilizers, careless littering and other forms of deliberate dumping, and effluent from our septic systems that seeps down to the groundwater that feeds ponds.

Mercury enters our ponds from polluted air carried by westerly winds, contaminated by coal-powered and trash-burning energy plants. While there has been some reduction in the pollutant-causing activities, mercury persists. (Before consuming any fish caught in a freshwater pond, refer to the MA Department of Public Health’s advisory postings).

Pond health is also at risk from the changing climate. Extreme rainfall events can overwhelm stormwater management systems and cause erosion, dumping pollutants, nutrients, and sediment into ponds. Warmer water temperatures and excess nutrients change the biology and chemistry of pond habitats in favor algal blooms and low oxygen, sometimes resulting in fish kills.

Cyanobacteria, also called blue-green algae, are ancient organisms responsible for creating the first oxygen on the earth. Cyanobacteria are commonly found in ponds; however, under certain conditions yet to be fully understood, they can produce toxins that pose health issues to animals and humans. Warmer temperatures with excessive nutrients contribute to toxic blooms (also called Harmful Algal Blooms [HABs]) that make swimming and other contact dangerous.

APCC has developed a cyanobacteria-monitoring protocol with the assistance of scientists from University of New Hampshire and the Cyanobacteria Monitoring Collaborative. Working with volunteers from pond groups like the Brewster Ponds Coalition and Friends of Chatham Waterways (and their respective town departments), data are being gathered as a means to document potential blooms and contribute to better understanding of cyanobacteria. APCC is working on a rapid assessment program to better inform communities when toxicity is present so the public can be advised about potential health risks.